In 2010, I talked with Lou Mallozzi at Experimental Sound Studio (ESS) in Chicago about the possibility of doing an archival project there. I had already worked with ESS on mastering two previous projects — American Winter (2007) and Silent City (2009) — both released on Chicago’s Atavistic label. Lou was generous and engaging, and offered me the chance to work with the Sun Ra / El Saturn Collection housed at ESS. The collection has over 500 audiotapes from the 1950s to 1993 of the experimental composer and bandleader Sun Ra. Along with several other artists, filmmakers, musicians, and writers, I was to create a new sound installation mixing archival recordings and my own ensemble. I was beside myself with excitement.

A few weeks later, an iPod arrived in the mail, along with a three-ringed binder. The iPod contained the entire Sun Ra / El Saturn collection, over 500 tapes and miscellaneous recordings. It was, to say the least, overwhelming. I remember the anxiety this small object produced. There was no systematic way to listen to everything in the short amount of time that the recordings were available to me. So, remembering the lessons I had already learned with other archival collections, I gave up and dove in.

That time in my life was as overwhelming as the tapes. My wife Jen and I were moving into a new house, our son Henry was just two years old, I was still teaching in an MFA program at Goddard College in Vermont, and I foolishly chose that exact time to enroll in a PhD program at Ohio University. Perhaps that chaos and busyness forced me to concentrate my work on the Sun Ra project, and to make decisive decisions with the material (knowing full well that there were hundreds, if not thousands more options to choose from).

What at first felt random soon yielded patterns. Rehearsal tapes, performances, and some commercial recordings were all linked together. Here, I marveled at Sun Ra’s ability to lead his Arkestra, stopping and starting songs in order to give out orders or make subtle adjustments with the ensemble. Slowly I began to recognize voices and matched them with instruments. The personalities and camaraderie of the performers became audible on the recordings.

Another set of tapes focused on Sun Ra’s speeches, poetry, and spoken word. On one tape, Sun Ra mysteriously reads his own poems through a phone, only to be recorded on the other end. It must have been an experiment with both the words and the medium of their delivery. On another tape, Sun Ra is giving a lecture, and I could hear him scratching away on a chalkboard as he created connections between homophones (and near-homophones, plus additional words connected only through Ra’s logic alone): “path, pathetic, pitiful, a way, reap what you sow, it is so, so, positive, positive-fied, so mad, delving into your soul…”

Other tapes were more confusing. Why was there a recording of a beer commercial? Did Sun Ra make recordings of television shows he was watching? Is that Sun Ra playing Debussy’s Clair de Lune? News programs, radio broadcasts, talk shows, UFO experts, and space-age self-help tapes all seemed to tie into the greater collection only because of Sun Ra: he was the thread through it all. I was determined to place these strange and often contradictory recordings together, alongside my own newly composed music, as both a sonic portrait of Sun Ra and as a dialogue between past and present.

Slowly, I made a catalog of the recordings that resonated with me. I made short transcriptions, too, noting their rhythmic and melodic patterns, and keys (if any). I asked a quartet of musicians — Fred Lonberg-Holm, Jeff Kimmell, Aaron Michael Butler, and Jeremy Woodruff — to record themselves responding to fragments of tape that I sent to them (along with short notated passages). The recordings they sent back to me became its own archive; I delighted at their attempts to play along with the Arkestra, and to add their own improvisational voices to the mix. Then, I collaged everything together, sometimes adding up to five or six layers of each instrument. Throughout, Sun Ra was the glue that held everything together. I let his voice remain in the recordings, intentionally not cutting it out. When he counted off to begin a piece or gave orders to a musician, we also responded to him, some forty or fifty years later.

The initial sound installation took place in 2010 at Audible Gallery in Chicago, along with a live solo performance. A 7” recording of three extra tracks from the project was released in 2012 on Scioto Records, called The Sociophonic Key. And then the Star Faced One album was released in 2013 on Atavistic Records. We premiered the project at the Wexner Center for the Arts here in Ohio (the ensemble included everyone on the recording; you can listen to live recordings from that performance here). That concert also featured a performance by Lonnie Holley, one that I’ll always remember; from the first note, Holley’s singing deeply affected me.

When the The Star Faced One came out, I was so surprised and grateful when Mojo Magazine named it their “Underground Album of the Year.” And I also couldn’t believe that it got so much support from radio stations both here in Europe and here in the US (especially my favorite, WFMU, and especially from DJ Trouble there, who still plays a track from it on occasion). I also deeply appreciated a short animated film that my good friend and artist Jo Dery made for the album release. She got permission to photograph the covers of the tapes and reels from the Sun Ra Collection, and she collaged them together. It is still a joy to watch!

In the past decade, I’ve loved observing how Sun Ra’s influence (along with concepts like “Afrofuturism”) has continued to grow and affect our culture. I see it in the amazing music of Damon Locks’ Black Monument Ensemble, and in Cauleen Smith’s beautiful films and astonishing installations. There are so many others, too. (If you’re curious, I wrote about these artists and others for the Danish journal SoundEffects. It is a few years old, but you can read that article here.)

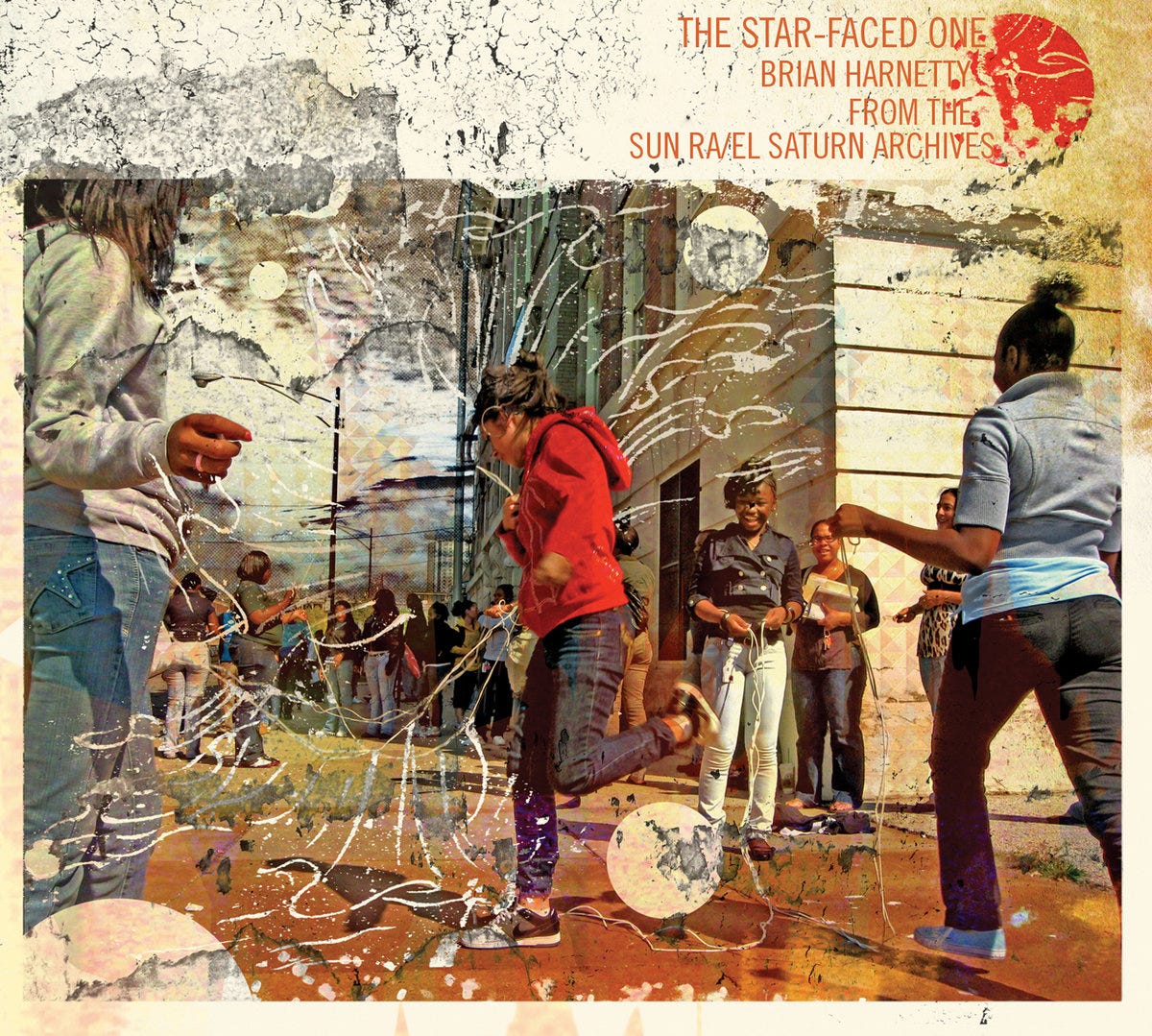

You can listen to or purchase The Star Faced One on Bandcamp (there are still some CDs available, too). You can also hear it on all streaming platforms. The cover, by the way, is a painting by Damon Locks, and was part of his work influenced by the Sun Ra Collection; in my opinion, it is the most amazing album cover I’ve ever seen (I’ll admit that I am biased, though).

I hope you’ll take some time to listen to the album—I am grateful that I had the chance to work with the Sun Ra/El Saturn Collection, and am stupefied at how a decade can pass so quickly!

Best wishes, and happy listening —

Brian

P.S. The title The Star-Faced One, by the way, comes from two sources. One day, I was sitting in my studio listening to Igor Stravinsky’s Zvezdolikiy. It is often referred to in French as Le roi des étoiles (“The King of the Stars”), but the original Russian translates to “The Star-Faced One.” At the same time (go figure), I was reading John Zwed’s biography of Sun Ra, Space Is the Place. The front cover shows a picture of Ra wearing star shaped sunglasses, and I put two and two together…

This is so good, we are jealous of it! Hahaha!