First, a quick note: For folks in Ohio, I will be performing a solo set from Words and Silences this Thursday (September 28) at the Granville Center for the Arts. The concert is free, and you can learn more about it here. If you are new to this project, you can watch these videos I made last summer at Thomas Merton’s hermitage in Kentucky (of particular note is the storm that came in while I was playing on Merton’s front porch, in “Breath, Water, Silence”). If you are able, I hope to see you in Granville!

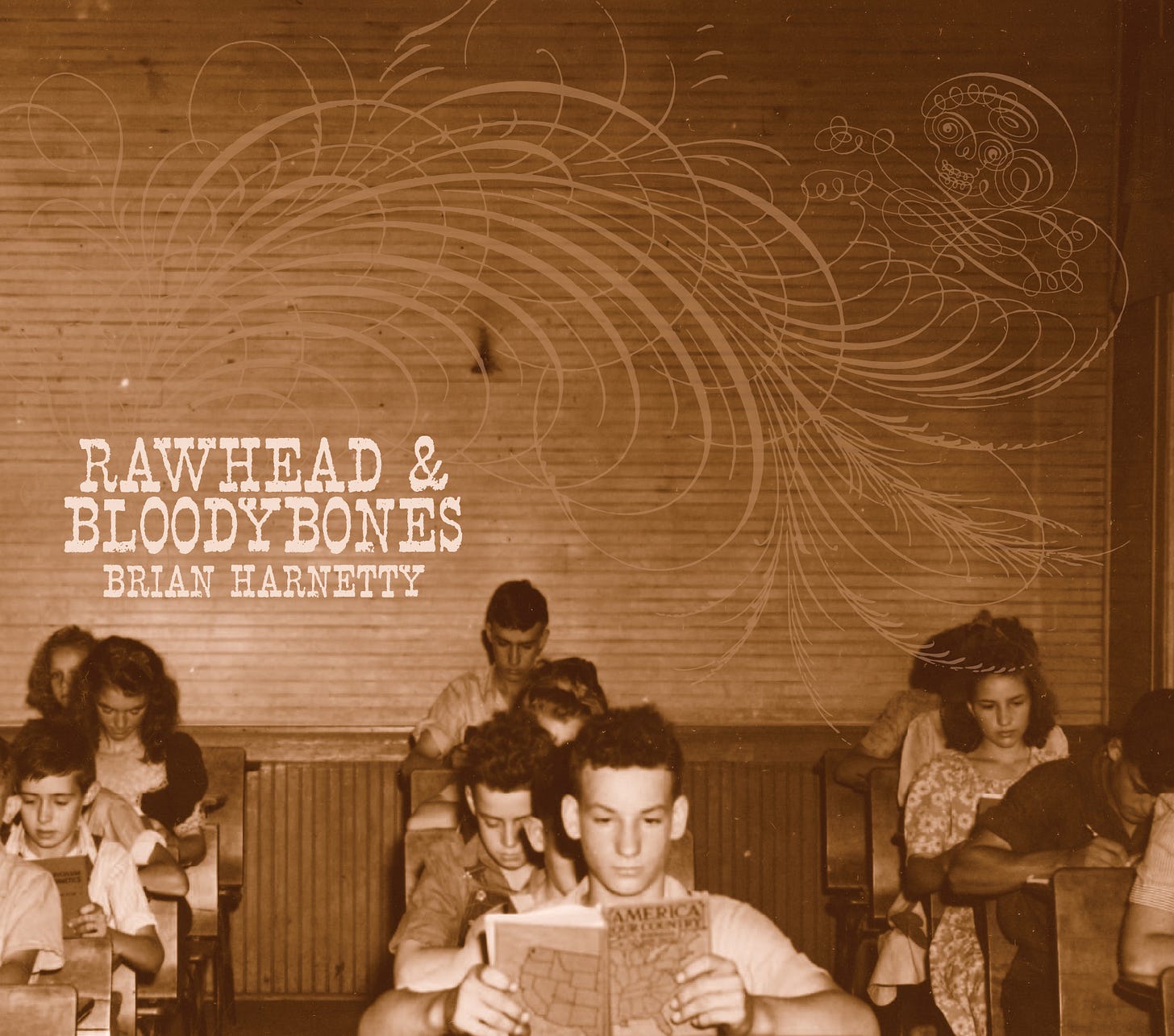

I’m also happy to share that I've added the album Rawhead & Bloodybones to my Bandcamp page. This means that for the first time you can now access my entire digital discography in one place.

Originally released on Dust-to-Digital in 2015, Rawhead & Bloodybones was the final album in the “Berea Trilogy” — projects that came out of the time I spent working in the Berea Appalachian Sound Archives in Kentucky (the other two, American Winter and Silent City came out on Atavistic Records in 2007 and 2009).

Rawhead & Bloodybones brings together folk tales mostly told by children and recorded by Leonard Roberts in the 1940s. The tales are humorous, gruesome, and full of meaning and character. They are weaved together with archival samples and newly composed instrumental parts. The combination of youthful voices and often-grisly tales is a striking contrast, one both beautiful and, well, creepy.

To celebrate, I'm offering 25% off the digital album, or 50% off if you purchase the entire digital discography. I also have a few physical copies of CDs if you still like physical objects (with design and layout from Color Quarry, who also did the design for Words and Silences). When it came out, Andrew Male at Mojo Magazine gave it 4 stars, saying it was “a spectral music box jazz-for-voices, imbued with a deep eerie poignancy.” And the writer and critic George Grella noted that the album “is a dialogue between past and present, memory and action, grisly, strange, and compelling.”

I also asked poet and scholar Keith Tuma to provide the liner notes to the album. I’ve reprinted them here, as they offer a good introduction to the folktales and the larger context of the project:

“Seven miles north of Hyden, Kentucky there’s a town called Dryhill. Locals know it also as Hell for Certain, or Hell-fer-Sartin, as you’ll find it spelled in South from Hell-fer-Sartin: Kentucky Mountain Folk Tales, the best-known book by folklorist Leonard Ward Roberts. The folk tales that Brian Harnetty samples in Rawhead and Bloodybones can be found there.

Roberts collected his tales “on the north side of the Pine Mountain range,” driving from town to town in his jeep, fearing already in the late 1940s and early 1950s that the way of life keeping these old stories alive was about to disappear: “I had little difficulty in finding an electrical outlet for my tape recorder.” Roberts went to schools to record “informants,” as he calls them. At the school in Hyden, he found Jane Muncy, aged 11, who’d heard “Merrywise” from the grandmother raising her, and Janis Moran, 12, who tells “Jack and His Master” for us here seventy years later.

In the back of his book Roberts lists parallel stories and versions for the tales and catalogs their motifs, following the Aarne-Thompson classification system. The source texts are mostly English and Anglo-Celtic, with splashes of German and French. Grimm and Perrault are regularly cited. Scholars will want to know these things, but it is the idioms and rhythms and timbre of the telling, the encounter between language and voice that Roland Barthes famously described as “the grain of the voice” that must have mattered most to Harnetty as he embraced these tales. Repetition and symmetries ease their telling, as with all oral traditions, and the music recognizes this: if it’s gold combed out of the good girl’s hair it’s snakes and frogs falling from the bad girl’s.

Then there are the journeys with much to endure—hiding from Jack and His Master in a blood-hole, only to have the severed ring finger from an old woman they’ve captured land in your lap. Or you are lowering your bucket in the well and fish up skulls that want to chant for you: “Wash me dry me lay me down.”

Nobody is the least bit perturbed by these gruesome happenings, least of all the narrators who rattle off the tales with such precocious professionalism. Jane and Janis are obviously delighted to be performing for their audience, for the tape recorder of Roberts. Their tales tell us that human butchery and sudden death exist side by side with goodness and luck, and they celebrate the resourcefulness and courage that used to be called pluck: “I told you to get out of my water bucket and hush” one heroine says to a chattering skull.

Harnetty’s music is equally calm and nuanced and wise in its response, as practiced as its models, which include not only these voices but also the fiddle music that cranks up in occasions for performance so very long ago and once upon a time but present for us again here.”

Happy listening —

Brian