In 2005, I spent a summer at the Headlands Center for the Arts in California. On an old army base just north of San Francisco, the Center feels like a secluded island despite being close to a large city. The resident artists had run of the place, and even though I had the entire gymnasium as a studio, I spent just as much time outside as in.

I began hiking the trails that surrounded the base. I walked among Eucalyptus trees as they rubbed together in the wind to sing their eerie (and pungent) songs. I roamed the old concrete fortifications buried into the hills looking West across the ocean, and took naps in human-made divots in the grass; perhaps they were remnants of a military plan to hear the enemy as they approached. I also walked along the shores of the bay, where the sounds of the waves and ocean were new and exciting to someone who grew up in a land-locked Midwestern city.

One night, I decided to stay up until dawn recording the frogs surrounding a pond. In the early evening, I set up my recording gear, and I waited. As darkness settled in, I began to regret my idea. We had been amply warned of mountain lions, and suddenly the quiet and remoteness of the landscape made this encounter with a lion very much possible. I was terrified, and hadn’t made any plan to deal with that possibility or any other encounters with wildlife other than to just sit still and listen. So that’s what I did.

The silence of the night became louder and louder. At first, there was just one frog calling out. Then another joined in, followed by more and more until the air was full of peeps and croaks. I listened to their patterns emerge and disappear. Just before dawn, they tapered off in the same manner that they came in, gradually reducing to one solitary voice. Tired and very cold, and with the frogs ringing in my ears, I hiked back to my house only to see a blue heron soundlessly standing alone in the field in front of me, observing me as if I was some kind of novel wildlife.

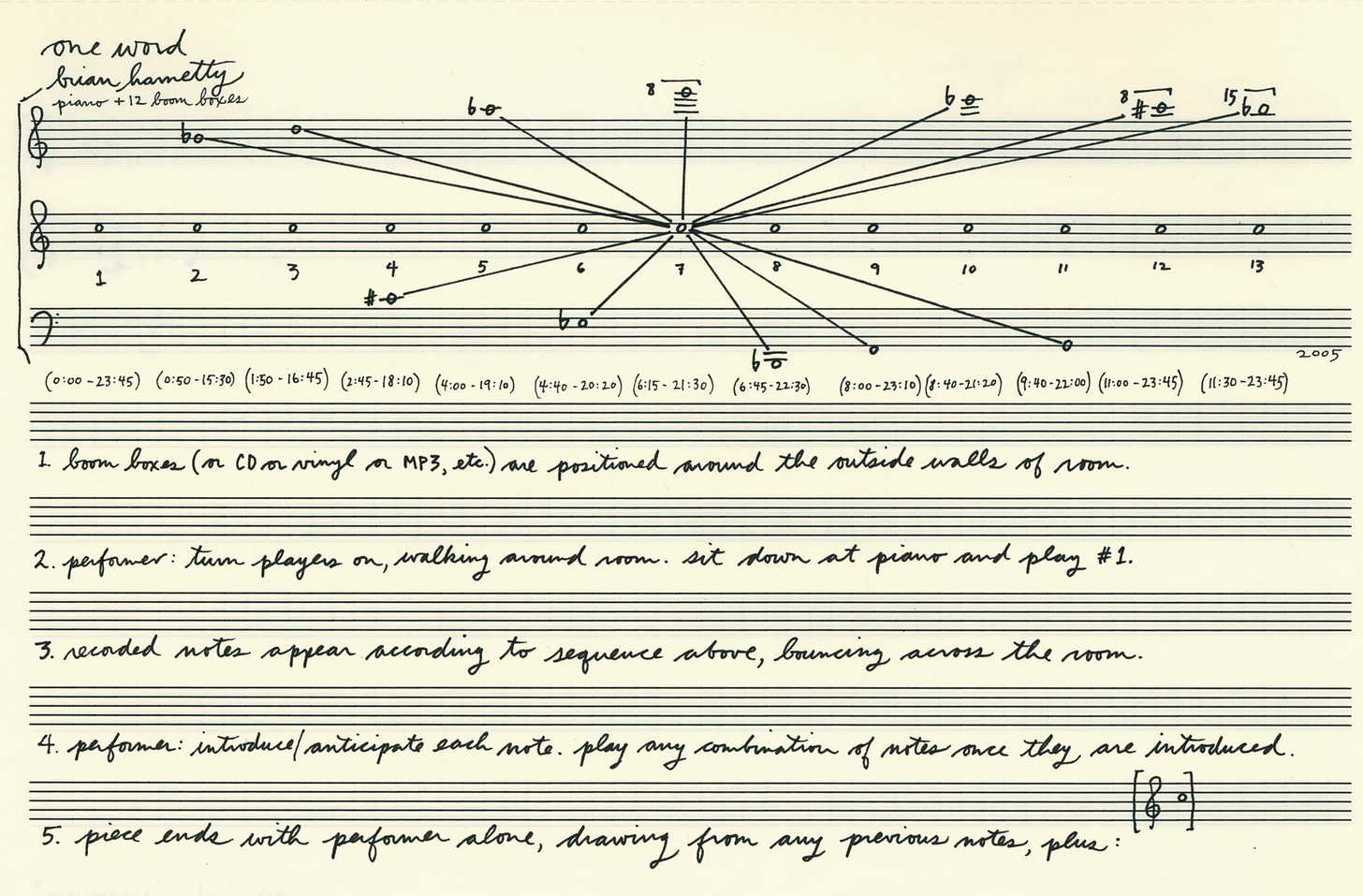

A few days later, I was recording piano for a music performance called One Word. The piece consisted of twelve single notes from the piano, each note recorded separately and projected through a boom box (I had noticed that each artist studio was equipped with one, and after some promises and bartering, the other artists begrudgingly shared theirs with me). A thirteenth note, one to thread all of the others together, was played live on the piano. I decided to record late at night, since it was the only quiet time to record the piano. I was also having trouble concentrating during the day, and the nighttime solitude helped clear and focus my mind. Many weeks had passed since I arrived and it had taken me as long to quiet myself enough to listen to the rhythms and patterns of the Headlands: social, natural, environmental, biological.

I thought again of the frogs, and how their performance was a perfect sonic curve, moving from silence to abundance and back again over the course of the night. I transcribed their patterns, mimicked them, and something different came out of the process.

You can listen to the entire recording of One Word here:

I recorded the first single note for one minute. It felt like a long time. I heard the piano’s sustain pedal creaking in the large room. I listened to the note strike, decay, fill the room, disappear.

A second note joined in, anchored to the first. Then a third, a fourth, and I lost track of time. I felt disoriented, dizzy. The piece grew simply, organically, evoked by the rhythms of the Headlands. One Word didn’t sound like frogs, but it did ebb and flow, subtly echoing the aural shape of their all-night singing. The landscape of the place worked its way into the structure of the music.

At that time, I was reading The Cloud of Unknowing, a classic mystic book from the fourteenth century. It was a guide to contemplative prayer, offering monks ways to let go of knowledge and move toward experience. It helped them to forget and unlearn in order to arrive at a place to open up to the world. Perhaps this “unknowing” is another form of silence, accessing something that is always present but normally ignored or out of reach, yet nevertheless is key to a deeper understanding of our existence.

In that book, I found a sentence that resonated with me: “If you want to gather all your desire into one simple word that the mind can easily retain, choose a short word rather than a long one.” In my mind, one word became one note, where even the act of making a piece of music became a contemplative experiment aiming to get at the noisy silence and unknowing of the night.

Later that summer, I performed One Word at the Headlands Center open house. I set myself up in a large room with a piano, and with the twelve boom boxes (once again reluctantly but kindly shared with me) placed in a wide circle. I positioned myself at the piano and waited. There were a lot of other activities going on during the open house, and I was not surprised that only a few curious people came in and sat down. A few minutes before the performance, however, a large bus pulled up outside. I could see it out of the window. Nearly fifty children tumbled out and filled the room with murmurs, shouts, and conversation. Perhaps they were on a school trip. Not wasting any time, I began walking around the space, turning on the boom boxes, playing corresponding notes on the piano, and listening. I was uncertain how the piece would even turn out. Even more unnerving (and exciting) was the fact I found myself in front of an unexpected audience with very different ears from my own.

Children aren’t known for being quiet. Yet what happened next shocked me: their rapt attention was so strong it was palpable. What is he going to do next, they were thinking. The piece gradually, subtly, quietly unfolded over a half hour. It demanded patience that I knew would test the limits of the children’s focus.

As I performed I listened intently. After a while the children understandably became restless. They started to fidget and I waited for — and then responded to — the next shoe-squeak, whisper, stifled cough, twitch, giggle, creaking chair, yawn, sigh. Their actions became a part of the piece. This busload of bubbling children unwittingly joined the boom boxes, the recordings, and myself at the piano, shaping the piece in ways I could not have known or predicted. Their rhythms added to the rhythms of the old army base, disrupting and unsettling my own preconceived plans, and my only response was to pay attention, to listen, and to focus on that one word as a way to disappear, to slip into that cloud of unknowing.

One Word was born out of the quietness and silence of the landscape: fog, hills, frogs, ocean. The children in their listening and energy filled the room with something else: a charged intensity that crackled across everyone there. The music slowly receded back to nothing, and we were left with only the sounds of the room, spectators milling about outside, and a distant fog horn. The children left, their chatter echoing off the walls as they walked down the hallway and out of the building. And I sat there, still and spent, listening for the silence.

Happy listening —

Brian

I have always been in awe of the delicacy and beauty of your work, as well as the deep thought involved and your remarkable ability to both listen and hear the world around you. Thank you, as ever, for sharing your work.